When companies are busy talking up their employer of choice credentials in order to attract skilled workers, it’s perhaps too easy to believe that the historic divisions between capital and labour have been not just diluted but subsumed by new sense of partnership.

The idea that your workplace functions as one big happy family pulling together is positively appealing – right up to the point when its overseas owner decides to outsource your entire department or the need for greater ROI sees the whole shooting match moved to Guangzhou. What is certain is that the industrial relations (IR) environment is more complex than simple ‘us and them’ version of boss/worker class warfare and the forces affecting it often lie outside the individual workplace.

That we’re competing in globalised world against low-wage economies is problem both for employers and employees – and finding effective recipes for increasing the size of New Zealand’s economic pie rather than squabbling over how it gets divided is paramount for both groups.

Sadly, the management-union relationship is most often portrayed when it’s at its worst – where individual workplace skirmishes or mass actions from health workers have hit the headlines. Successful negotiations that bring win-win solutions may be more common but they’re not the ones most people read about. So while various strikes and lockouts tend to reinforce the them-and-us characterisation, the bigger picture is much less black and white. Yes, there is still the age-old divide between capital and labour as to where the rewards flow, says business commentator Rod Oram.

“But the much more interesting view is that we’re all in this together. Business can’t do without labour or capital so the question is how to get that relationship right, get the best response out of both and maximise the return to both. When people start thinking in those ways, that’s when really interesting things can start to happen.”

So just where is the relationship at today – and where is it going?

In New Zealand, the environment has had its share of legislative nudges and for unions it is still before and after story – of the riches to rags variety. Okay, not quite riches, but their role of representing workers’ interests back in the 1980s was uncontested, union membership was strong and they had vital presence in the IR landscape.

Then the 1991 Employment Contracts Act deregistered unions, precipitating fall in membership which only halted when their legal status was restored by the Employment Relations Act at the turn of the century. Since then recovery has been slow and uneven: union density languishes around the 21 percent mark (down from over 50 percent prior to 1991) and is heavily skewed toward the public sector where one in every two workers is unionised. In the private sector, that proportion drops back to one in 10.

Meanwhile, the IR ground has shifted. Human resource departments have plugged some of the labour advocacy gaps by adopting “softer” employee management policies in growing recognition of the seemingly obvious – that workers perform better if encouraged and inspired rather than being controlled and coerced.

The industrial ground itself has also shifted. Sectors where union representation was at its strongest – jobs at the gruntier, heavy industry end of the work spectrum – are in decline while those in the much more fragmented service sector are growing. And in more individualised workforce, unions are sometimes seen as bit outmoded. Even the language is problem – talk of ‘collectivism’ seems to hark back to Marxist-flavoured era that has little resonance in today’s world.

UK research suggests that unions are struggling to overcome the “stale, male and pale” stereotypes that just don’t appeal to workforce that’s more diverse, better educated and more concentrated in the service sector.

The reality – certainly in New Zealand – is somewhat different. With the public service dominating union membership, today’s typical unionist is more likely to be tertiary-educated woman. And local research suggests one of the biggest challenges facing unions is indifference.

A 2003 study (NZ Worker Representation and Participation Survey) found that nearly half of all respondents and up to 85 percent in non-unionised workplaces either reckon unions offer them no value or would actually harm their cause. That picture hasn’t changed much since, according to one of the researchers Peter Boxall, professor of management and human relations at the University of Auckland Business School.

“Most workers in the private sector just don’t see unions as being relevant to their interests.”

A healthy employment market, with overall low unemployment and skills shortages showing up in many sectors, hasn’t exactly helped the union cause, notes Boxall.

“Employers already feel obliged to embellish the offer and that gets laid in as new set of expectations so the labour market is working well for employees.

“However there are areas out there where workers feel more vulnerable and want union representation but can’t get it. So there is representation gap as well. Our research showed significant minority in non-unionised workplaces would like to be in trade union but that option isn’t available to them.”

That aside, the majority of workers in the private sector are getting on, getting ahead and doing it for themselves, says Boxall. “That’s not an environment in which trade unionism is going to grow.”

Which isn’t to say unions no longer have place in the industrial relations picture.

“They definitely do have place but it is just not mass movement and can’t pretend to be because it is not meeting with mass demand,” says Boxall.

“Today’s workforce feels lot more secure and many more people are developing themselves as individuals. It’s more about personal growth – you do that course or move to that place where you can get the experience you want. People don’t see that as something trade union can do for them.”

Are unions still force?

So does that mean that employees have been managing to get their fair share of the fruits of their labour without union intervention?

Not necessarily – and the division is often far from even handed.

Speaking at recent conference in Europe in support of an Australian opponent of that country’s new “work choices” legislation, Council of Trade Unions president, Ross Wilson* likened it to New Zealand’s IR environment under the Employment Contracts Act.

“During this period the density of collective bargaining was significantly reduced and the disparity between rich and poor rose quicker in New Zealand than in any other developed country.”

Workers could no longer rely on national award or regional agreement to set basic standard for wages and conditions – that floor was taken away and even skilled workers lost ground, says Laila Harré who heads the National Distribution Union (NDU).

“One of the conundrums lot of external commentators have identified in New Zealand is that while we have skills and labour shortages, we’re not seeing significant gains in pay and conditions and I think lot of damage was done to workers’ confidence to bid for what they’re worth in the labour market. It demonstrates, I think, that individuals are never going to have the confidence to bargain for what they’re personally worth – they need some system and structure around that, which is what collective bargaining supplies.”

There’s also sense that the demands of work have intensified and that more people are putting in longer hours for diminishing share of the overall returns. The growing pressures for business services to be available 24/7 is running up against employee need to balance the demands of their work with those of family or outside work interests, notes PSA national secretary Richard Wagstaff.

“Those two tensions are not easily compatible. Flexibility is good but who is in control of it?”

Business owners don’t want the viability of their

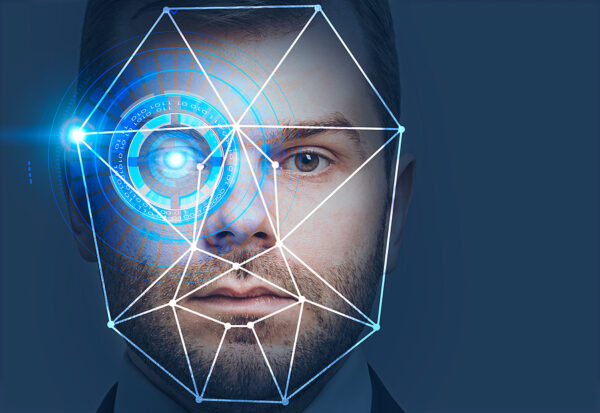

Privacy Commissioner announces intent to issue Biometrics Code

The Privacy Commissioner has announced his intention to issue a Biometrics Code, has released the Biometric Processing Privacy Code for consultation and is calling for submissions on the draft code