While New Zealand Exchange (NZX) chief executive Mark Weldon last month bemoaned the current drop in the volume of share trades, some observers are asking if there is more to the collapse than just slowdown in the economy. Are public listed companies losing ground to private equity?

The private equity market in the United States last year invested US$302 billion compared with about US$100 billion just four years earlier. And in Australasia, private equity firms are growing just as rapidly and becoming much larger and more central part of our business landscape. Here in New Zealand, as Management magazine went to the printers, Australian private equity investor CVC Asia Pacific was making $160 million takeover offer for local fast-food company Restaurant Brands.

According to Auckland-based investment banker Rob Cameron, the shift is an outcome of the stifling and costly impact of excessive governance regulation and compliance. “The private equity market is becoming more competitive,” he says. “Private equity now represents the ‘natural’ alternative to the open [public] corporation.”

Cameron believes private equity firms are getting “increased attention” from investment bankers and other transaction advisers because their “decisive style and increasing share of transactions” make them attractive to deal with.

And rather than simply impeding economic growth and employment, as some commentators claim, poorly conceived and implemented regulation of publicly listed companies is:

* driving more talent and financial resources to private equity firms; and

* leading to the ‘eclipse’ of the open corporation as the dominant form of business organisation.

A growing number of companies are asking the question: why go public? Cameron thinks there are good reasons why more companies now, and increasingly, will reject the public listing option.

Increased governance regulation is at the heart of growing sense of organisational dissatisfaction, according to Cameron. There is, he says, presumption that poor financial performance and lost investor confidence in the US are the result of problems with market regulators and that “market failures” are endemic to the capitalist system. There is also belief that failures can “only be addressed by regulations requiring increased compliance with good practices”.

A few corporate failures do not constitute market failure. And, says Cameron, the recommended solutions seldom address what practitioners see as the key challenges facing boards in fulfilling their governance role and responsibilities. In his opinion, poor regulatory responses will “stimulate” shift to “closed” (private) organisations at the expense of “open” or public listed companies with dispersed shareholdings.

In broad sense, investors are having to think about what is the most appropriate organisational architecture to deliver high performance in today’s market. Organisational architecture is concerned with two issues in particular:

* how to ensure the most capable people have both the authority and the information they need to make the best decisions; and

* how to ensure that all organisational decisions are aligned with the objectives of the business and its owners.

There are, broadly speaking, just two forms of organisation – closed and open. The first includes sole proprietorships, partnerships, private companies, cooperatives and private equity firms. Open corporations on the other hand, usually have wide dispersal of ownership and are often publicly listed. The difference between the two relates primarily to the degree of separation between ownership and control.

There is limited separation between ownership and control in closed corporations, whereas the opposite applies to open corporations in which ownership and decision making are specialised and delegated – the division of board and management.

In open corporations owners are specialist risk bearers and don’t need the detailed specific knowledge necessary to make key decisions. Boards and managers become specialist decision-makers with the owners appointing board of expert directors as their primary control mechanism over the enterprise.

Boards put in place performance measurement, reporting and reward systems to make sure the decision-makers act in the owners’ interests. Ultimate responsibility for the company’s performance rests with the board, while the owners reserve the right to remove the board and/or the chair in the event performance falls below expectations.

However, as Cameron points out, an open organisation’s ability to capture the benefits of specialised decision making and responsibility depends on the market for managerial and direct talent, equity capital availability and the market for corporate control.

Cameron has spent time looking at open corporations and the performance inhibitors they encounter in the international market. And when it comes to governance and regulation he says two major points emerge.

“A global ‘one size fits all’ approach to corporate governance laws and regulations is not appropriate,” he says. “The diversity among countries’ legal and economic environments, differences in robustness and responsiveness of equity capital, corporate control and talent markets and variations in local governance practices require case-by-case evaluation of proposed regulation.

“And the most important role for boards in countries with ‘high quality’ legal and business environments is overseeing wealth creation – wealth allocation is important but secondary. board’s performance is not enhanced by ‘compliance’ mentality to regulation,” he says.

So when it comes to looking at New Zealand’s governance regulation, Cameron thinks regulatory enforcement agencies should take into account that the country has high quality legal and business environment with general respect for the law, an efficient judiciary and “corruption index” which is among the lowest in the world.

And given that our equity capital markets are robust and responsive with institutional investors, market analysts and shareholder advocates taking an increasing interest in the quality of firms’ governance; that the corporate control market is “alive and well”; that our market for managerial and director talent is “thin”, and our corporations are small by international standards with compliance costs having relatively large impact on profitability and value, we should be cautious about further regulating corporate governance.

“Simply put, specific regulation of corporate governance practices holds major risks for the open corporation compared to an environment which provides and enforces adequate rights and protection for all shareholders and clearly specifies responsibilities, fiduciary duties and liabilities of directors, requires accurate and timely reporting, and supports robust and responsive equity capital and corporate control markets,” says Cameron.

“Corporate governance codes can contribute to achieving this environment provided they are not mandatory and operate on ‘comply or explain’ basis; are developed through discussion and consensus among regulators, market participants (including boards and managers) and professional organisations; and focus on the board’s role in creating value – in addition to the well-canvassed issues of fairness (to shareholders), accountability, transparency and responsibility for the interests of minority shareholders and other stakeholders.”

Private equity poses “real threat” to public corporations, according to Cameron. As the British magazine The Economist pointed out in recent feature on the topic; “the private equity industry has moved from the fringe to the centre of capitalist action. In the 1980s private equity was place for mavericks and outsiders. These days it attracts the most talented members of the business, political and cultural establishment including many of the world’s top managers.”

In Cameron’s opinion, the ability of these organisatio

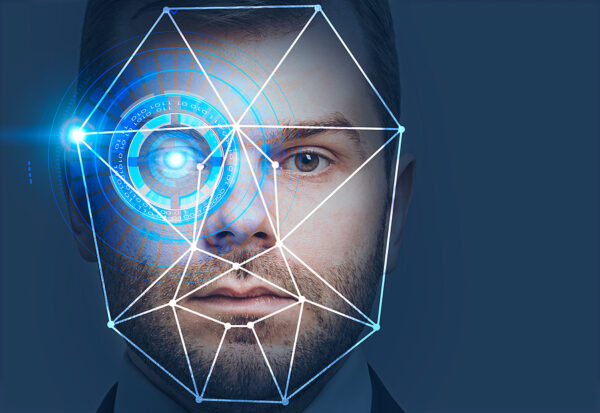

Privacy Commissioner announces intent to issue Biometrics Code

The Privacy Commissioner has announced his intention to issue a Biometrics Code, has released the Biometric Processing Privacy Code for consultation and is calling for submissions on the draft code