Boards of directors are under pressure to lift their performance – more so since the GFC hit and the recession lingers. Directors must, as recent McKinsey Consultancy’s Global Survey put it, “take more responsibility for developing effective strategies and overseeing business risk”.

The research I have been doing for my new book, kind of sequel to my Complete Guide to Good Governance and Great Governance books, has revealed five key lessons that I believe directors should focus on to deliver better governance in future.

The first, and perhaps the most important, is board composition. The recession has shown in spades that organisations seriously suffer from lack of independent board membership. And while I appreciate that New Zealand struggles with the limited gene pool from which to draw competent directors, boards must make greater effort to think outside the “old boy network” for new blood.

There is serious lack of relevant diversity in the composition of our boards. They simply do not consist of the best possible mix of individuals with relevant skills such as experience, competencies, background, perspectives, age, gender and ethnicity. The lesson is: get the right people on the bus. There have been far too many non-paying fares filling seats.

Boards should regularly identify the best mix of the attributes identified above. To elaborate on the gender issue for example, women comprise only 9.3 percent of directorships in NZ Management magazine’s Top 200 companies but make up half the nation’s total labour force and 64 percent of our tertiary graduates. Something is askew there.

The same bias applies to age representation. Boards suffer from lack of younger directors with their fresh thinking, youthful perspectives and mindset, their specialised knowledge and more recent education. more diverse ethnic mix would deliver important different perspectives and experiences to board tables. Diversity brings relevant strategic views and competencies to add value to the performance of the organisation – business or public sector.

The second lesson comes from examining what boards do. There is lack of director clarity about their role at the board table and that led, and still leads, to ineffectual governance practices. Directors are too often unclear about the board’s role, about the extent and nature of the board’s involvement in strategy, performance oversight and in managing risk.

Effective governance has little to do with regulators and laws and everything to do with what transpires inside the boardroom. If directors want to avoid repeat of the disasters of recent history, they must improve their performance in the key governance roles and responsibilities of:

• Strategy – short and long term

• Oversight of performance and fiduciary

• Oversight of risk management

• Ensuring compliance.

Uncertain board environments will, in my opinion, deliver new paradigm of unpredictability and uncertainty in what is an increasingly complex commercial world.

To be clearer about their role, directors must understand exactly what oversight means. It means they must monitor, review, examine, inspect, supervise, watch and take responsible care. Good governance, therefore, means effective board oversight of strategy implementation, performance (including fiduciary and financial status) and risk management.

It is insufficient for boards to merely note out-of-line performance. Directors must ensure appropriate and timely action is taken to correct performances that are out-of-line with expectations. Trust, but verify.

Safeguarding future performance is the overriding aim of performance oversight. But word of caution – don’t get involved in management. Governance is about “what” not “how”.

And now the sensitive lesson – chief executive performance and remuneration. Rather more offshore than here, the abuse of governance in this quarter of board responsibility is painfully apparent. But the lessons are just as relevant here. Greed and hubris are insidious human failings and boards have duty of care to society to keep them in check.

In short, boards did not act responsibly in respect of chief executive remuneration. Remuneration’s relationship to organisational performance is fundamental. There is no question that chief executive should be fairly rewarded for what she or he achieves. The GFC showed that incentives, in steadily growing number of cases, encouraged high risk taking at the expense and often to the ultimate demise of the enterprise.

Chief executive non-performance is one of the most important issues any board must deal with. Directors cannot ignore continuing poor performance. Boards must identify, counsel and, if necessary, terminate an inadequately performing chief executive.

Lesson number four is about compliance with directors’ duties. Too many directors lack comprehensive understanding of their obligations and as result fail to practise proper compliance. Directors must comply with their obligations and duties but often fail to do so.

Directors’ key duties come from the:

• New Zealand Companies Act 1993

• Organisation’s own constitution

• Financial Markets Authority Act 2011

• Securities Act 1978

• NZX Listed Companies Listing Rules

• Financial Reporting Act 1993

• Other relevant legislative and regulatory requirements.

Powers of governance apply to the board but the duties apply to individual directors. Boards must monitor changes in relevant laws and confirm that the company and the board comply with new or different requirements. The Financial Markets Authority Act has, for example, new powers under which finance company directors can be sued on behalf of investors.

But these duties are not the purpose of governance – they are the rules of the road. Directors should not use compliance obligations to deter them from their primary duty which is to act in the interests of the company and to grow wealth.

The fifth lesson the recession has delivered is all about evaluating the performance of board and commitment to continuous governance improvement – both of which are clearly lacking and contributed in no small measure to the crisis and the current recession.

To facilitate continuous improvement in organisational governance, directors must ask themselves five things:

• How effective is this board’s leadership and governance?

• Is this board functioning at the highest standards and levels of performance?

• In what ways could the board/chairman/individual directors improve their effectiveness and functioning?

• How well is the board performing in relation to the current and future needs of the company and its shareholders?

• Is the board able to report to the shareholders on their performance?

These questions can only be answered by formal evaluation against agreed performance criteria. Evaluation is not report card that rates against some abstract scale, rather it provides means to continually improve the effectiveness of the organisation’s leadership and governance.

At the beginning of the year boards should establish set of performance criteria. Each director and the chief executive should retain copy and use it as the basis for their personal ongoing “criteria of performance” reference.

At the end of the year directors should privately evaluate the board’s, the chair’s and each individual director’s performance against the criteria.

A board evaluation review meeting should then identify and agree what changes or actions would improve the functioning of the board and the chairman. Individual directors might privately discuss the evaluations of their performance with the chair.

Follow-up follows. Directors agree on the improvements, changes in processes or procedures, the education or training needed or changes to the board meeting and, in some instances, director’s tenure.

I am still researching my new book. These five lessons are, in my opinion, at least some of the truths the recession can teach those direct

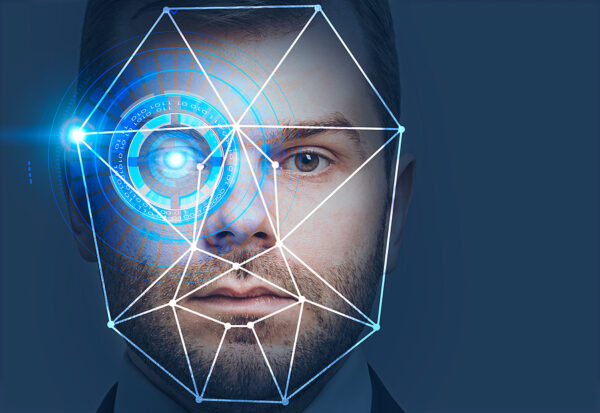

Privacy Commissioner announces intent to issue Biometrics Code

The Privacy Commissioner has announced his intention to issue a Biometrics Code, has released the Biometric Processing Privacy Code for consultation and is calling for submissions on the draft code